Following the Leeuwin’s unintentional sighting in 1622, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) showed little interest in colonizing the region. To them, this was a coastline of foul ground, jagged reefs, and little commercial value. However, as the 17th century progressed into the 18th and 19th, this accidental landmark became the centerpiece of an intense maritime chess match between European powers.

After the Leeuwin mapped the cape area, the following ships explorered the southwest coast.

The Dutch: The Coast as a Warning (1627)

Impression of the ship 't Gulden Zeepaert exploring 't Land van Pieter Nuyts

Five years after the Leeuwin, François Thijssen aboard the 't Gulden Zeepaert found himself swept even further south. Unlike the Leeuwin, which turned north toward Indonesia, Thijssen’s ship was pushed eastward along the bottom of the continent.

For nearly 1,800 kilometers, he tracked the coastline, marking the first major survey of Australia's southern edge. Accompanying him was Pieter Nuyts, a high-ranking VOC official. They named the vast, desolate stretch Nuyts Land. While they provided the first real sense of the continent's scale, their reports of "dry and cursed" land ensured the Dutch would not return to settle. The South West remained a warning to sailors to turn north before the Roaring Forties pushed them too far.

The French: The Floating Laboratories (1792–1801)

By the late 1700s, the French arrived with a completely different mindset. They weren't looking for spices; they were looking for knowledge.

Carte generale des terres de Leeuwin et de Nuyts

D’Entrecasteaux (1792): While searching for the lost explorer La Pérouse, his ships, the Recherche and Espérance, battled the massive Southern Ocean swells. Near the point now known as Point D'Entrecasteaux, his crew marveled at the monstrous granite cliffs. His cartographer, Beautemps-Beaupré, created charts of the reefs so precise they are still admired by hydrographers today.

Nicolas Baudin (1801): Baudin’s expedition was a massive scientific undertaking. His ships, the Géographe and Naturaliste, carried 22 scientists and artists. They spent weeks in the calm waters of Geographe Bay, just north of Cape Leeuwin. They were the first Europeans to describe the Tuart forests and the unique wildlife of the Leeuwin-Naturaliste ridge, sending crates of seeds and specimens back to France for Empress Josephine.

The British: Matthew Flinders and the Final Map (1801)

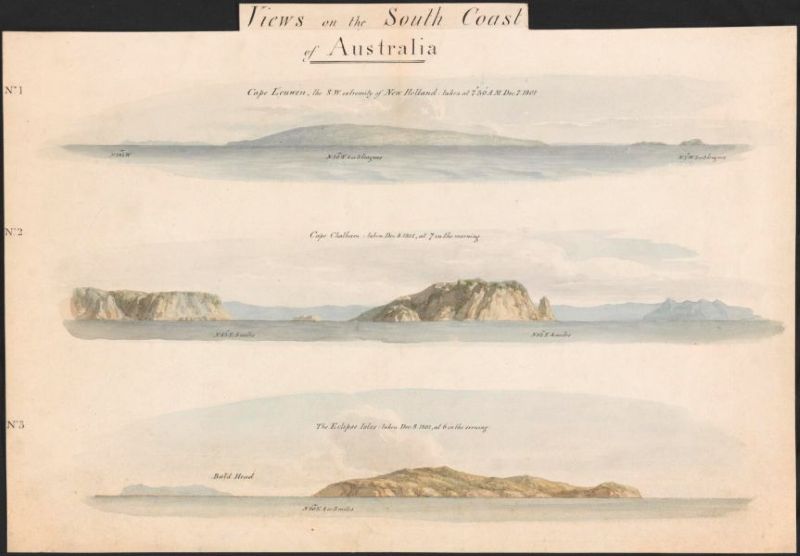

Views on the south coast of Australia by William Westall

As the French were cataloging plants, the British sent Matthew Flinders to claim the map. Arriving in the HMS Investigator in December 1801, Flinders was the first to realize that all these scattered sightings—Dutch, French, and British—belonged to one single, enormous continent.

At the southwest tip, Flinders paid homage to the very first accidental sighting. He looked at his Dutch charts and officially named the point Cape Leeuwin (Cape of the Lioness). Seeking shelter from the treacherous surf, he anchored in the bay to the east (Flinders Bay). Here, his crew finally stepped onto the shore to replenish their wood and water supplies, turning a century of distant sightings into a physical landing.

Onboard the Investigator was the famed botanist Robert Brown. While the sailors filled water casks, Brown and his team scrambled over the granite rocks and through the dense coastal scrub. They collected dozens of species of plants never before seen by European science, including various types of Proteaceae and coastal heaths.

Flinders described the area as being "covered with a coat of grass and shrubs," noting the majestic Karri and Marri forests that loomed in the distance behind the coastal dunes. He described the soil as "sandy," but noted the abundance of birdlife, particularly black swans and various ducks.