The Noongar (also spelled Nyungar, Nyoongar, Nyungah, or similar variations) are the Aboriginal Australian people who have traditionally inhabited the southwest corner of Western Australia, a vast region known as Noongar boodja (country). This area spans approximately 200,000 square kilometers, extending from Jurien Bay in the north, east to beyond Moora, and south along the coast to Esperance, including major centers like Perth (Boorloo), Albany (Kinjarling), and Bunbury (Koombanup). The name "Noongar" translates to "person" or "people" in their language, specifically referring to the original inhabitants of this southwestern region, which represents one of the largest Aboriginal cultural blocks in Australia. Archaeological evidence, including sites like Devil's Lair near Margaret River, confirms Noongar presence in this area for at least 45,000 to 50,000 years, with no indications of other groups occupying the land prior to European arrival.

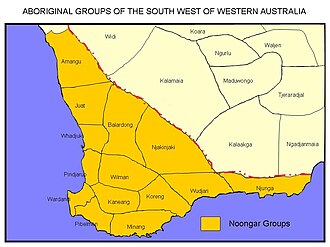

Noongar groups

Noongar society is divided into 14 distinct dialectical or language groups, each tied to specific ecological zones and territories: Amangu (northwest), Yued/Yuat (northern coastal), Whadjuk/Wajuk (Perth area), Binjareb/Pinjarup (Murray River region), Wardandi (southwest forests), Balardong/Ballardong (wheatbelt), Nyakinyaki (northeast), Wilman (Collie area), Ganeang (southeast), Bibulmun/Piblemen (southern forests), Mineng (Albany region), Goreng (east), Wudjari (southeast arid), and Njunga (far east).These groups share a common cultural and linguistic foundation but maintain unique identities linked to their boodja.

Pre-colonial Noongar life was semi-nomadic, with family groups (moort) occupying and managing specific tracts of land in harmony with the environment. They relied on seasonal resources, trade routes (such as the ancient path now known as the Albany Highway), and a deep spiritual connection to the land, viewing it as an extension of themselves "Ngulla boodjar, our land". Today, Noongar people number around 40,000, continuing to assert their cultural identity, rights, and traditions amid ongoing revival efforts.

Historical Background

Noongar history is marked by millennia of sustainable living followed by profound disruption from European colonization. Prior to contact, population estimates range from 6,000 to tens of thousands, with communities living in balance with nature through practices like fire-stick farming to regenerate vegetation and facilitate hunting. European exploration began in the early 17th century, with Dutch sailors like Pieter Nuyts in 1626 naming the southern coast "Nuytsland" and observing Noongar camps and fires. French expeditions in 1792 and 1803 noted sophisticated fish traps along the coast, mistakenly assuming Noongar people subsisted solely on saltwater resources.

British settlement commenced in 1826 at Albany and formalized in 1829 with the Swan River Colony under Captain Charles Fremantle, claiming sovereignty over Noongar lands. Initial interactions were tense; in 1827, James Stirling encountered armed Noongar men expressing anger at territorial incursions. Resistance was fierce, led by warriors like Yagan (son of Midgegooroo), who defended boodja and was killed in 1833, his severed head was displayed in England until repatriated in 2010. The Pinjarra Massacre in 1834, orchestrated by Governor Stirling, killed dozens of Noongar to quell opposition. Further atrocities included the Wonnerup Massacre in 1841 and the use of Rottnest Island (Wadjemup) as an Aboriginal prison from 1838, where over 300 Noongar men died from harsh conditions.

Colonial policies evolved from nominal "protection" in the 1830s (e.g., mounted police and superintendents) to assimilation and control. The 1886 Aboriginal Protection Board enforced segregation, while the 1905 Aborigines Act enabled child removals, creating the Stolen Generations, thousands of Noongar children were forcibly taken to missions like Moore River (1918–1951), where 346 died. Reserves were established but often revoked in the 1920s–1930s, dubbed the "Second Dispossession." Noongar men enlisted in both World Wars but were denied citizenship and benefits upon return. The 1936 Native Administration Act imposed eugenic measures to "breed out the color," and assimilation policies persisted until the 1950s.

Post-1960s advancements included the 1967 referendum granting citizenship, the 1972 Aboriginal Heritage Act protecting sites, and the 1992 Mabo decision enabling native title claims. The Single Noongar Claim, lodged in 2003, was recognized in 2006 as evidence of continuous connection to land since 1829, upheld on appeal in 2008. This culminated in the South West Native Title Settlement (2018–2021), Australia's largest, valued at $1.3 billion, encompassing six Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) for regional corporations: Yued, Gnaala Karla Booja, Karri Karrak, Wagyl Kaip Southern Noongar, Ballardong, and Whadjuk. Managed by the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council (SWALSC), it empowers Noongar self-determination.

Language

The Noongar language is a Pama-Nyungan family tongue spoken across the entire southwest, with regional dialects corresponding to the 14 groups. It features words like "boodja" (country), "moort" (family), and "kaartdijin" (knowledge). Colonization suppressed it through missions and policies, reducing fluent speakers to a handful today, though thousands know phrases and many identify with Noongar heritage.

Revival efforts intensified in the 1980s–1990s via community festivals (e.g., Marribank 1985, Dryandra 1992) and the establishment of the Noongar Language and Culture Centre in Bunbury (1986). A standard orthography was adopted in 1997, shifting from "Nyungar" to "Noongar." The Noongar Boodjar Language Cultural Aboriginal Corporation (NBLC) leads ongoing work, producing dictionaries, grammars, books, courses, and interactive resources to teach all generations.

Social Structure and Kinship

Noongar society is family-centered (moort), with extended families managing specific boodja for hunting, gathering, and ceremonies. Boundaries were fluid, allowing overlaps and trade, but access required permission from local leaders (bridyer or boordier). Kinship is matrilineal, divided into two moieties: Manitjimat (white cockatoo) and Wardangmat (crow), inherited from the mother to prevent close intermarriage and ensure genetic diversity. For instance, a Wardangmat man marries a Manitjimat woman, and offspring belong to the mother's moiety. This system governs marriage, inheritance, land rights, and obligations, with men often traveling far for spouses.

Elders (boordier or yeye), both men and women, are knowledge custodians, teaching through oral traditions and earning respect via community consensus. Mutual obligations emphasize reciprocity: sharing resources freely with kin, caring for in-laws, and prioritizing elders in food distribution. Breaches invoke retributive justice, like spearing or ostracism. Kinship extends to land stewardship, with families as guardians of sacred sites.

Spirituality and Dreaming Stories

Noongar spirituality is rooted in Nyitting (the Dreaming or cold time), an eternal creative period when ancestors shaped the world. Central is the Wagyl (also Waugal or Waugal), a snakelike Rainbow Serpent spirit that emerged from the earth, creating rivers (e.g., Swan/Derbarl Yerrigan, Canning), lakes, hills (Darling Scarp), and landforms while depositing rocks as its droppings and forests from its scales. The Wagyl resides in waterways, ensuring fresh water and life; Noongar are its appointed guardians, following protocols like throwing sand into water before drinking or avoiding murky pools to prevent sickness. Sites like Bolgart Spring or Herdsman Lake are sacred entrances for spiritual leaders (boolyada maaman) to commune with it.

Dreaming stories convey moral lessons and knowledge. One example is the tale of Bullung (pelican) and Bulland (crane), where the pelican's greed leads to punishment, teaching sharing. Another describes the Wagyl's journey from flat, barren earth, awakening to carve valleys and fill them with water, then entering the ground to watch over creation. Spirits like Djinga (evil) or Bulyit (hairy man) enforce taboos: no whistling at night, no playing with fire after dark, and children must travel in pairs. Spirituality integrates with daily life, viewing all elements (rocks, trees, sky) as purposeful and interconnected.

Seasons and Environmental Knowledge

Noongar recognize six seasons (bonar), dictating migration, food sourcing, and activities for sustainability:

- Birak (Dec–Jan): Hot/dry; controlled burns to clear scrub for hunting reptiles and honoring ancestors

- Bunuru (Feb–Mar): Hottest; fishing in estuaries, gathering fruits

- Djeran (Apr–May): Cooler; collecting bulbs/seeds, ant activity signals ceremonies

- Makuru (Jun–Jul): Wettest/coldest; inland hunting, fertility season

- Djilba (Aug–Sep): Transitional rains; hunting emus/possums/kangaroos, collecting roots

- Kambarang (Oct–Nov): Warming/wildflowers; fishing frogs/tortoises/crayfish, birth season

This knowledge, tied to lore, promotes biodiversity through practices like avoiding overharvesting or eating totemic animals.

Traditional Practices: Food, Hunting, Gathering, Tools, and Weapons

Noongar were hunter-gatherers, adapting to diverse ecosystems, coastal, forests, wetlands, and semi-arid zones. Food sources included kangaroos, wallabies, emus, possums, turtles, fish, crayfish, birds, bulbs, seeds, roots, fruits, and honey. Hunting involved tracking and communal drives, with men using spears for larger game and women gathering plant foods. Gathering emphasized sustainability: taking only what was needed, using fire to promote regrowth.

Food preparation included roasting over campfires (kaarla), wrapping in bark, or grinding into pastes. Meals were communal, reinforcing social bonds.

Art and Cultural Expressions

Noongar art encompasses paintings, carvings, dance (corroborees), and song, often depicting Dreaming stories and land connections. Rock art at sites like Mulka's Cave or Wave Rock illustrates Wagyl narratives. Kinship dictates artistic rights: specific moieties or families "own" certain stories, restricting who can depict them. Corroborees involved rhythmic dancing and singing, distinct from eastern Aboriginal styles, for ceremonies, storytelling, and social cohesion. Modern expressions include protests (e.g., 1970 Swan Brewery site) and digital platforms like Kaartdijin Noongar.