The name of Sir James Mitchell will always be associated with the iniquitous Group Settlement Scheme. If his enthusiasm for the scheme could have replaced scientific theory or considered investigation, the scheme may well have succeeded, but alas this ill-considered project was doomed to failure before it began.

The aim was to open up the sparsely populated south west of the State for dairying in order to reduce dependence on imports from interstate. The fact that the rainfall was good and the forests dense and luxuriant was considered a good enough indication that any sort of agriculture would prosper there. Even at that time, more investigation would probably have advised against the scheme. In the event, things unknown then such as deficiencies of trace elements in the soil were a mysterious and insidious killer to crops and animals. But this came later…

The Scheme began in 1921 and initially targeted families in Australia, but after the signing of the joint-venture Migration Act between the British and West Australian governments, recruiting in Britain began in earnest.

In 1923 the advertisements in the English press that encouraged potential Group Settlers were so fulsome in their descriptions of what a settler could expect that even today it would be easy to recruit eager takers. “Own your own farm” they offered, showing bright pictures of grassy landscapes, healthy bronzed people and comfortable houses.

In 1923 the advertisements in the English press that encouraged potential Group Settlers were so fulsome in their descriptions of what a settler could expect that even today it would be easy to recruit eager takers. “Own your own farm” they offered, showing bright pictures of grassy landscapes, healthy bronzed people and comfortable houses.

The shock of reality must have been overwhelming when these hopeful families, after a more or less pleasant voyage, a less than pleasant stay at a hostel in Fremantle, a gritty train ride and a bumpy lurching cart ride through impenetrable and unfamiliar forests came to a rough clearing where a few windowless corrugated-iron humpies baked in the heat. Some women, in particular, never recovered from this initial horror. Most of the settlers, however, persevered with the incredibly hard work, heat, dirt, flies, ants, isolation, poverty and deprivation. And that’s the wonder of the Group Settlement Scheme.

Under the supervision of a Group Foreman, the men were directed to partly clear and fence and provide a water supply to each of the farm blocks. Only then were the characteristic four-roomed timber houses erected and the families could move from the humpies. Groups were usually made up of 20 locations, each of about 160 acres, depending on the terrain. This block of land was “free” apart from survey and office costs of £13.1.0, to be added to the costs of the voyage, the eventual group house, all farming implements and animals. It is not hard to see that this debt, given the poor productivity of the land, would soon become unsupportable.

Many settlers left. By 1924, about a third of the initial settlers had walked off their potential farms. Many others only stayed because they had no other option.

Sustenance payments were made to the families until their farms became viable, and the families struggled and persevered. In all the deprivation and discomfort, nevertheless the children of the Groups flourished and their recorded memories are of carefree times – hard work, yes, with milking before school and a three or four mile walk to it – but as one of those children observed, when you’re all poor, you don’t know you are. Some of the teachers at the one-room schools showed huge ingenuity and a dedication to education that is positively awesome. They were remembered with huge affection by their students and surely deserve accolades. They coped with the teaching of up to six or seven levels of student classes, cared for the children when flood and fire threatened, and often instilled into the children a huge respect for their surroundings through innovative “nature study” lessons.

The school building became the social hub for the Group, with dances, Christmas parties and other gatherings taking place there. Tennis courts would be constructed beside them in time to create another aspect of community participation.

By the late twenties the Group Settlement Scheme was such a drain on State finances that all politicians wanted to abandon it. The management of the Scheme was passed to the Agricultural Bank, who reassessed the settlers’ indebtedness and in many cases provided the last straw to the struggling farmer.

When the depression came in the 1930s the price of cream, the mainstay of the settlers’ income, dropped and some farmers who had persevered this far finally broke and left.

Miraculously, there were still some remaining. Consolidation of the inadequate acreages created more viable properties, and there are still an amazing number of old group farms still extant in the Shire.

The houses built for the Groupies were sometimes lost to bushfire or accidental burning, some moved to other locations, some left to decay, some extended and built on to and still happily lived in today. (See Current Projects – Group House Project) They are the only remainders of the Group Settlement Scheme apart from the flourishing dairy industry that the settlers did, in spite of everything, begin.

Settlers Group 2, 1923, visited by Prime Minister Bruce and Lady Bruce. James Michell centre rear.

Group Settlement house with immaculate vegetable garden, date unknown.

Cowaramup Siding, 1924. Carts lined up for distribution to Groups.

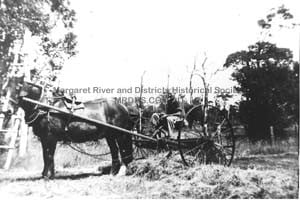

Hay-carting on a Group 72 farm in 1927

Abandoned Group Settlement farms often became Soldier Settlement farms after WW2. This photograph taken at Kudardup in 1953

See also group settlement names and map